Australia entered a new automotive era on January 1, 2025.

The arrival of a carbon-dioxide (CO2) reduction scheme added a new and important influence on what new vehicles will be available in Australia in coming years and what they will cost.

You’re probably already aware of the New Vehicle Efficiency Standard’s introduction given the amount of debate that went on leading up to its legislation in late 2024.

There was plenty of disinformation (that’s just plain lies, folks) and misinformation (stuff that’s wrong, but not intentionally so) and that’s to be expected given how much lobbying, arguing and proposing of alternatives was going on. Selling cars in Australia generates big bucks, don’t worry about that.

In the end, the stark reality is this. Climate change is real, the impact of transport CO2 emissions is a significant contributor to that and Australia needs to play its part in reducing it. After all, the USA has had fuel economy rules (CO2 reduction by another name) since the 1970s. Up until January 1, it was pretty much only us and the Russians amongst developed economies who didn’t worry about this stuff.

Which means, basically, we’ve got a long way to go to catch up.

Here, we’ve compiled an NVES explainer, which we’ve tried to keep as simple and understandable as possible.

The NVES is meant to reduce CO2 emissions from new light vehicles powered by internal combustion engines and, therefore, encourage car companies to offer Australian car buyers more choice in terms of more fuel-efficient vehicles and EVs.

The scheme covers passenger cars, SUVs, utes, and small vans up to 4.5 tonnes gross vehicle mass (GVM). We’re talking about the sort of vehicles most buyers are shopping for in your dealership, not the big vans, trucks and buses used entirely for commercial purposes.

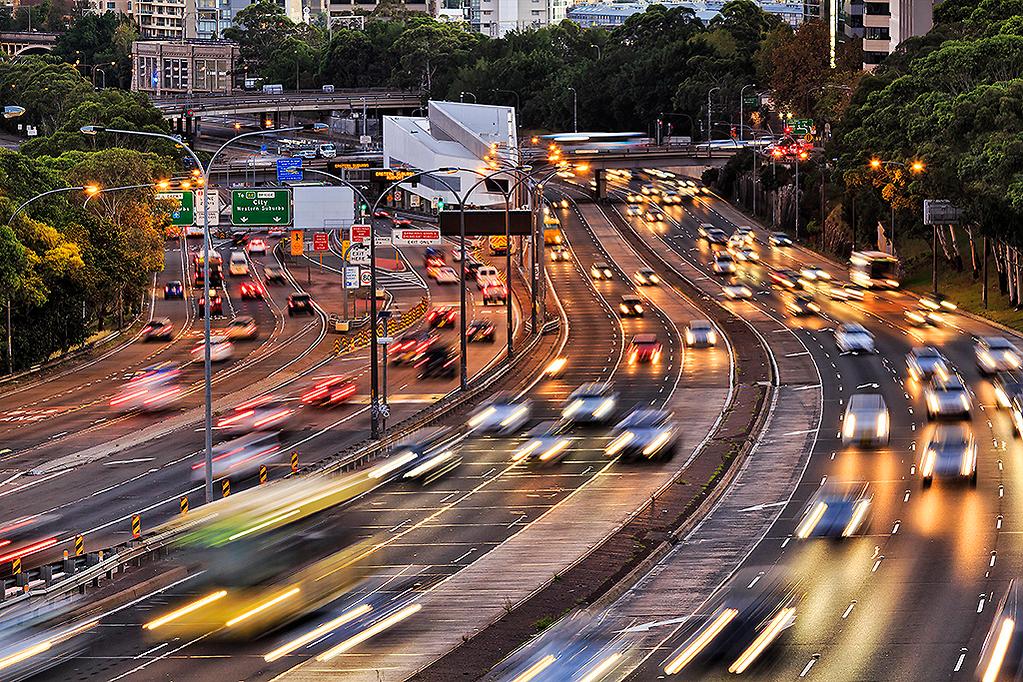

CO2 reduction is important because as we all know, Carbon Dioxide is a greenhouse gas. That means it traps heat in the atmosphere, triggering rising global temperatures. The more we pump into our atmosphere, the more temperatures rise and the environmental scale gets tilted towards disaster. Light vehicles are estimated to contribute 10 per cent of all CO2 emitted into the atmosphere by Australia each year. The federal government has announced a net zero CO2 emissions target by 2050 and has flagged the NVES as integral to achieving that.

The combined emissions average of each model in an automotive brand’s line-up is measured against the CO2 emissions target set by the NVES. The target reduces annually.

The CO2 combined emissions average for each model is based on testing to achieve Australian Design Rule (ADR) certification – not manufacturer estimates.

The total number of each model incorporated into the combined CO2 calculation is based on how many unique Vehicle Identification Numbers (VIN) are issued by the federal department of transport’s Register of Approved Vehicles (RAV) within the audit period – so how many are imported, not sold.

Carbon credits are issued for beating the target – the more a brand undercuts it by the more credits they get. Dollar fines are issued for exceeding the target. The more they exceed it, the more it costs.

Essentially, across a brand, if their combined CO2 output is less than their combined CO2 target, then they’re in the clear. And if they have excess credits they can sell them to brands facing fines.

As an extreme example, an EV-only brand like Tesla that issues zero emissions will generate a surplus of credits, while a diesel-centric brand will likely generate fines.

It’s important to note that while the NVES kicked off on January 1 this year, vehicle emissions won’t be judged for credits and fines until July 1. It’s a bit of a warm-up period for everyone involved.

Even then, the NVES Regulator will measure vehicle emissions over three years. Sure, progress will be constantly monitored (by both the regulators and the car companies themselves), but a car company will have another two years to rectify its emissions and dollar fines won’t be issued until February 2028.

These credits have the ability to bolster a business’ bottom line. Tesla has generated $10 billion from selling off carbon credits to brands that can’t hit US limits.

For the debtors, the idea is to try and get back in the black within two years and/or buy the credits they need for less than the fines handed out after year three.

So, just how expensive are the fines, and how are they calculated? Well, the way they are calculated can be pretty onerous. Essentially, it will cost $50 or $100 per gram per kilometre of CO2 for each vehicle sold, which is over the target. The lower figure applies if the brand pays when the infringement notice turns up. Challenge it legally and lose, and it’s the higher figure.

The potential fines will increase quickly for a big seller like a popular diesel ute, especially if that OEM hasn’t got vehicles to redress the emissions balance.

This is an extreme example, but say a brand imports 10,000 examples of a model range that averages 70g/100km over the limit. That’s 10,000 x 70 x 100 (worst case scenario) = a $70,000,000 fine.

It’s worth noting that a brand might end up paying nothing or even being in the positive overall if it imports enough low and especially zero-emissions vehicles to Australia that undercut the target.

Brands can try to tilt the balance more in their favour by clumping their emissions results into larger automotive ownership groups. For instance, Stellantis has some high-emissions brands, including Jeep, but has also just launched the electrified brand Leapmotor in Australia, which will generate credits.

It’s also worth highlighting that emissions will become ever more stringent over the next five years, and both the rate and timing of the reduction have been a bone of contention throughout the heated debates ahead of the introduction of the NVES.

Also, the federal government has split vehicles subject to the NVES into two classes. Class 1 is for passenger cars and soft-roader SUVs. Class 2 is for large 4x4s that are body-on-frame construction and can tow more than 3.0 tonnes.

Within the two categories, the vehicles will be split into sub-groups depending on weight to determine their increasingly stringent emissions targets.

One of the most widely reported outcomes of the NVES is vehicle pricing. So, will car prices go up?

Opponents of the NVES say yes, and some say by quite a lot. Backers say no.

Meeting the NVES targets could mean importers have to sell vehicles here that have more expensive technology – so prices could go up. Fines could also eventually drive prices up for vehicles that fall on the dirtier side of the regulations, too, but that could take years to shake out, remembering that the NVES works in three-year cycles.

On the positive side, the credits accrued by low- and zero-emitting vehicles could help reduce their prices. The profits from selling those credits could be passed on to consumers through price reductions.

The other outcome is that models and brands altogether may go off-sale.

In a presentation backed by the Motor Trades Association of Australia and the Australian Automotive Dealers Association last year, US fuel standards expert Barbara Kiss outlined seven levers the car companies can pull in response to the NVES:

• Reduce the number of thirsty models in its line-up

• Import fewer examples

• Increase the price of thirsty models

• Swap to cleaner powertrain tech

• Buy credits

• Pay fines

• Exit the market

But if you think the number of brands in the Australian market will be significantly reduced, remember there are a bunch of low- and zero-emissions brands lining up to get into Australia, with five new brands on their way this year alone.

A modified version of this article originally appeared on carsales.com.au

Share this article:

Disclaimer:

The information presented in this article is true and correct at the time of publishing. business.carsales.com.au does not warrant or represent that the information is free from errors or omissions. The content is provided for informational purposes only and should not be construed as professional advice. For more details on our editorial standards and ethical guidelines, please visit our Editorial Guide Lines.